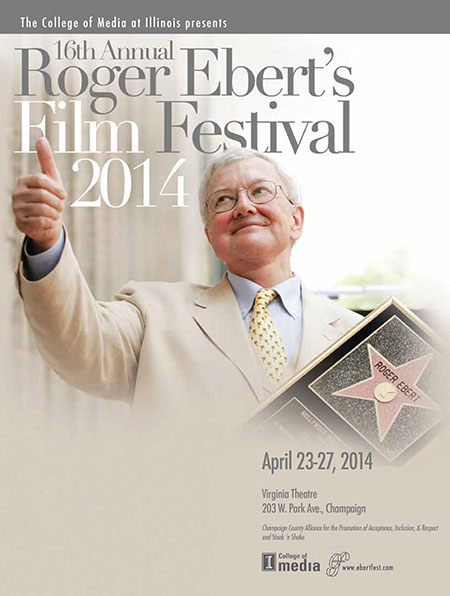

Article du C-U: Ebertfest ’14, pt.3

“Continuing the Campaign for Real Movies: On WADJDA”

After sending a battery of Confidential agents into the Ebertfest fold in April, we present their findings

by Sierra Marcum

~~~~~

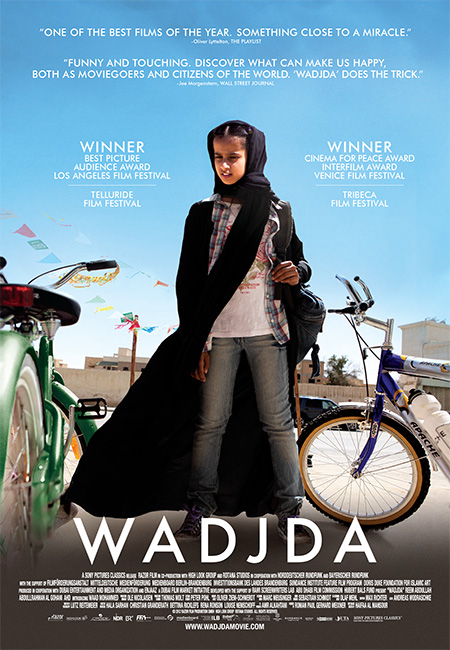

WADJDA, the first feature film shot entirely in Saudi Arabia, deserves its excellent critical reception because it is warm, honest, funny, moving, and skillfully crafted. It’s difficult to find anything negative to say because this film was so engaging to watch (and writer-director Haifaa Al-Mansour, so admirable to hear) at the 2014 Roger Ebert’s Film Festival. In all honesty, I’m reluctant to try. The pre-screening presentation quoted Ebert who wrote, “Empathy is the most essential quality of civilization.” WADJDA is precisely the kind of film he valued because it can expand our experience and understanding by putting us in unfamiliar shoes.

The first thing we learn about Wadjda (Waad Mohammed) is that she wears Converse sneakers with purple laces. They stick out next to her classmates’ Mary Janes. She also wears the modest black hijab worn by her classmates and all women in public, but listens to forbidden music and makes bracelets in football (i.e., soccer) team colors to sell to her classmates. (I found this detail especially relatable because my 12-year-old sister also makes bracelets and sells them to her friends.) Wadjda enters a Koran recital competition not because she’s particularly devoted, but because it’s the quickest way to earn the money for a beautiful green bicycle. She does this despite the fact that girls are not allowed to ride. Her irrepressible delight in this bike, along with her determination to earn and use it to win a race against her best friend Abdullah (Abdullrahaman Al-Gohani), drives much of the film’s optimism and emotional power. Her mission and her pluck in carrying it out consistently earned the “Ebertfest” audience’s most vocal reactions of appreciation and amusement.

During her post-screening interview and audience interaction, Al-Mansour emphasized two points that informed my own understanding and appreciation of WADJDA. First, she wanted to make an optimistic film that was emphatically not about victims or villains; by my reckoning, this goal contrasts sharply with the vast majority of on-screen depictions of the Middle East, or at least those common in the United States. In an interview with National Public Radio, Al-Mansour mentioned that a fellow Saudi’s response to the film was, “I understand, I feel how Americans feel now when they see an American movie.” WADJDA is important because, by resembling reality and being positive, it challenges dominant media messages about the Middle East and its culture.

It is easy for Americans to forget the ubiquity of our own media and the narrow range of stories about themselves portrayed on screen. No American understanding of WADJDA is complete without the realization that it meets a largely unmet need for positive representation of non-Western (in this case, Saudi) societies. The film suggests that Western media is ubiquitous in Riyadh, the capital city of Saudi Arabia, as well as further removed from Saudi reality than our own; a fleeting shot of a Western advertisement, tacked up inside a public women’s restroom door at the mall, shows a white woman in street clothes – pants and a sleeved shirt – with her chest and crotch covered by black censor boxes.

The second point Al-Mansour made was that she intended WADJDA to show how conservative Saudi values hurt people – not Saudi values or society as a whole. Attentive viewers will notice Wadjda’s mother (Reem Abdullah) has a friend who must belong to less conservative circles than those on which the film concentrates. Said friend works at a hospital with men. There, she covers her hair, but not her face.

Wadjda’s mother’s situation is the most heartbreaking and powerful example of the ways in which Saudi conservatism not only stifles young women but also harms entire families. She is distressed about, and ultimately very hurt by, the fact that her husband (Sultan Al-Assaf) visits only when he pleases. Despite his love for Wadjda and her mother, his parents urge him to take a second wife because his first cannot bear him a son.

Since women are not permitted to drive, Wadjda’s mother must rely on a hired driver to get to work. The strict school headmistress (Ahd) repeats that girls should be neither seen nor heard by men, and is forever commanding Wadjda to cover her face outdoors because she is nearing the end of her childhood. An older schoolmate’s education ends abruptly when she is caught meeting a young man alone. Girls are publicly shamed when the headmistress catches them painting their toenails together and construes their casual proximity as suspiciously, dangerously friendly. Wadjda must endure a construction worker’s leering and jeering while she plays with Abdullah. Her father indulges in good food and video games while her mother dutifully cooks and does the dishes. It is easy to see how the conservative Saudi society reflected in WADJDA seeks to control women by limiting their freedom to choose what they do, where they go, and how they dress. They are punished for failure or refusal to conform to conservative ideals of womanhood.

To Westerners, these restrictions are largely unfamiliar in both detail and degree of severity, but WADJDA gives us the opportunity to see that extreme Saudi social conservatism and extreme American social conservatism do not differ so much in character or message, at least with regard to gender. Like the society featured in this film, conservative American society demands that girls and women maintain a reputation for sexual purity in exchange for a fragile semblance of respect, view homosexuality as an aberration to be stamped out, and value men’s entitlement and related double standards that plague many families in many cultures. In America as in Saudi Arabia, girls and women are sexually harassed every day by strangers while school administrators often police girls’ clothing, holding girls responsible for men and boys’ desires. Conservative America may show a lot more skin than conservative Saudi Arabia, but a close look at WADJDA reveals their restrictive and hurtful messages have much in common otherwise. Empathizing with people whose culture is unfamiliar in some ways but similar in others can both help us understand that culture in an appropriately complex way and make it easier to recognize and talk about our own culture’s problems and injustices.

WADJDA is an especially admirable film because of the logistical and social difficulties Al-Mansour faced while making it. Movie theaters are banned in Saudi Arabia, so Al-Mansour resourcefully chose to screen the film in foreign embassies and a cultural center. Filming in Riyadh also presented some unusual challenges, as Al-Mansour noted at Ebertfest as well as in the distributor’s production notes. “I occasionally had to run and hide in the production van in some of the more conservative areas where people would have disapproved of a woman director mixing professionally with all the men on set,” she states in the latter. “Sometimes I tried to direct via walkie-talkie from the van, but I always got frustrated and came out to do it in person.”

Despite political and cultural obstacles, Al-Mansour dared to make the film she wanted to make. In doing so, she achieved something remarkable. WADJDA managed to clearly show Americans at Ebertfest what it was like to lack privileges we might take for granted in a manner that is realistic yet delightful and uplifting.

WADJDA played the sixteenth annual Roger Ebert’s Film Festival on Saturday, April 26, 2014, 11 a.m. Director Haifaa Al-Mansour appeared as a festival guest.

~~~~~

WADJDA is a production of Razor Film in co-production with High Look Group, Rotana Studios, Amr Alkahtani, Norddeutscher Rundfunk, and Bayerischer RundFunk, distributed theatrically, VOD, and on home video (U.S.) by Sony Pictures Classics. It was written and directed by Haifaa Al-Mansour and produced by Roman Paul and Gerhard Meixner, and stars Reem Abdullah, Waad Mohammed, Abdullrahaman Al-Gohani, Ahd, and Sultan Al-Assaf. 2013, Digital, Color, 98 minutes.

~~~~~

Sierra Marcum studied literature at Bennington College in Vermont and received her BA in 2013. She was born and raised in Champaign-Urbana, freelances as an editor, and is currently writing a coming-of-age novel.

Article © 2014 Sierra Marcum. Used with permission.

CUBlog edits © 2014 Jason Pankoke

Cover graphic: © Roger Ebert’s Film Festival/Daily Illini

WADJDA graphics:

© 2013 Mongrel Media (Canada) via Sony Pictures Classics