Article du C-U: Ebertfest X, pt.5

“The Big Ten”

Roger Ebert’s Film Festival reaches the end of a decade – but without its founder and host

by Anthony Zoubek

~~~~~

Dateline – Champaign, Illinois

Saturday, April 26, 2008

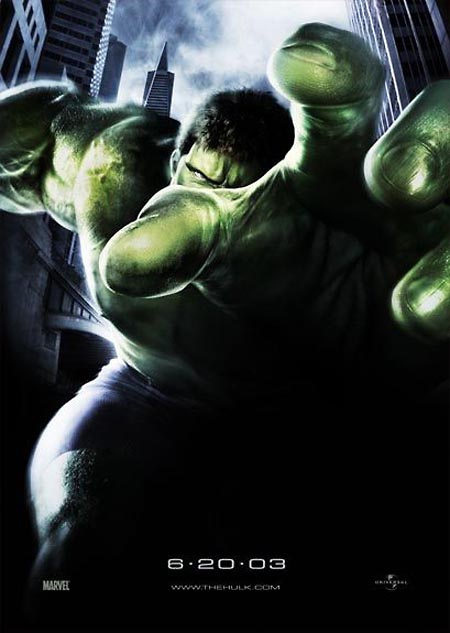

“I am proud to be a Fighting Illini … I’m also glad to finally be back in the theater where I first saw RAMBO II.” – Academy Award-winning filmmaker and University of Illinois alumnus Ang Lee, introducing his maligned comic book adaptation HULK.

~~~~~

THE IMPLIED TENET OF all 10 Roger Ebert’s Film Festivals so far – that overlooked cinema deserves a second chance – suggests a stigma of limiting festival screenings solely to art movies. Each festival features an onslaught of notably ignored indies – screenings of THE CASTLE and ME ANE YOU AND EVERYONE WE KNOW being the best, SONGS FROM THE SECOND FLOOR and TARNATION being the worst – in addition to at least one example of something so apparent on Roger Ebert’s end-of-year 10 Best lists that it’s become a cliché – the large-budgeted special-effects extravaganza that everyone but Ebert negates for having big, bold images overmatched by bigger, bolder intellectual ideas.

In some cases, Ebert’s appreciation for movies that equally define Hollywood excess as much as they characterize the visual glory of going to any movies, regardless of budget or star power, are right on the money. In 2000, the screening of New Line Cinema’s box-office dud DARK CITY beat the Virginia Theatre’s previous attendance record set in 1977 during the initial theatrical run of STAR WARS. Ebert did not merely laud the film for its intelligent thematic undercurrents, regarding the battle of acting on instinct versus acting on soul; he placed the film in the “number one” spot on his best-of-1998 compilation. DARK CITY has its place among other controversial titles on those lists – STRANGE DAYS (1995) comes to mind – nestled amidst “traditional” selections agreed upon by the film critic establishment as the year’s crème de la crème.

This is not to pompously insinuate that “Ebertfest” or Ebert’s lists should be limited to specific “kinds” or “types” of good and surprising films, or that either are in fact that limited. But every year, like clockwork, there is the minor controversy made by some Ebert fans regarding the one Hollywood special-effects film to which Ebert raises his thumbs that even the most savvy cinema savant will shake or scratch their heads over.

The 10th Ebertfest aimed to re-evaluate two such films, THE CELL (2000) and HULK (2003), one proving Ebert’s once-debatable praise was warranted, accurate, and ahead of its time, the other remaining as litigious and questionably acclaimed as it was the day Ebert (and few others) dared to give it four stars.

~~~~~

ALLEGORICALLY, IT WAS appropriate that HULK director Ang Lee made the joke about RAMBO II in his pre-show remarks to the festival’s Saturday matinee sellout crowd. RAMBO: FIRST BLOOD PART II (1985), a follow-up to the surprisingly potent FIRST BLOOD (1982), tried to use the iconic John Rambo’s bloody exploits in Vietnam as a foreground and façade to thinly veil political themes regarding hot-button interest in reconnaissance missions to rescue POWs during the 1980s. Viewed nearly 25 years later, RAMBO II is aesthetically bleak, boorish, bloated, and morally misguided, a fast-food-for-thought Happy Meal look at anti-Communism via Cold War sentiment in Reagan’s America. Its makers, including star Sylvester Stallone, the late director George Cosmatos, and co-screenwriter James Cameron, thought that peppering gore and gunfire with gourmet political commentary made their film a “smart” Hollywood blockbuster.

Now to the Virginia Theatre comes HULK, praised in the Ebertfest movie program as a Marvel Comics adaptation with “dramatic ambition,” a movie “for people who wouldn’t be caught dead at a comic book movie.”

He is wrong.

In trying to turn a jolly green giant with anger management issues into an Oedipal examination of wounded, emotionally-distant children with deep psychological bruises brought on by conflicted parents, HULK morphs into an overly-deep hodgepodge of bruised Hollywood egos, awful computer-generated effects, and laughable psychoanalytical scenarios that emotionally distance and ultimately conflict with the movie’s overall ambitions.

~~~~~

TO A LIMITED EXTENT, Lee willingly discussed these ambitions, and honestly addressed the film’s faulty approach in bringing these aspirations to fruition, in his pre-screening remarks and post-screening question-and-answer session.

“After indulging in the hidden dragon of Chinese culture – sexual repression – I chose to do a comic book,” Lee explained after a rousing introduction that included a participatory sing-a-long of the Fighting Illini fight song. “I thought, instead of sexual repression, let’s deal with violence.

“There is a misconception,” he continued, “that when you do a small film, it is passionate filmmaking and that a Hollywood film means you’ve sold out. Not so. This film dug very deeply into my subconscious.”

Made shortly after September 11, 2001, HULK tries to “take our post-9/11 psychology and imbed it in the context of a comic book,” Lee said. Giving credit where credit is due, the intended subtext of HULK helped it fit in nicely with the successfully employed thematic subtext of just about every other film screened at this Ebertfest: psychology, parent-child quandaries, coming to terms with plights of the Id, et cetera.

Where HULK fails, apart from its brilliant opening titles – the best “meaningful” credits sequence since the killer’s mad journal entries seen up front in SE7EN (1995) – is its inconsistent exploration of psychosomatic motifs, not helped by the emotional framework of the script. Eric Bana’s Bruce Banner, green with a bit more than just envy for Jennifer Connelly’s Betty Ross, is “an emotionally distant man” not by demonstration but rather Betty’s oral declarations. For as much “showing” of characterization demonstrated in the visually explosive CROUCHING TIGER, HIDDEN DRAGON (2000) and, to a lesser end, THE ICE STORM (1997), Lee’s HULK is all about telling us how its characters think and feel. Outside of saying to Betty, “I get angry – and I like it,” there is no proof that the Hyde side of Bruce’s persona is perhaps his true nature.

Hence, we have no sympathy for Bruce in his love for Betty or his participation in overtly CGI enhanced action sequences, including his battle with genetically mutated killer poodles in perhaps the most ridiculous scene in any comic book adaptation since the late Richard Pryor fought a killer robot in SUPERMAN III (1983).

Lee wants the comic book drama to intelligently cloak his psychodrama. Thanks to psychobabble strewn from the lips of characters featured in overused split-screen frames to make the movie “feel” like a comic book, there isn’t much of a cloak here. The multiple textures in HULK never meld. The promise and potential of Lee’s vision is admirable and we want it to work; its failure is saddening when the underwhelming special effects finally overtake any yearning for meaning and perspective.

For a long time after HULK bombed in theaters, “I tried to put this movie out of my psychology,” Lee said later during his post-screening commentary. “I did the movie and it was uncomfortable. The negative reception toward it went a little too deep. I felt hostility. Critics saw it and were angry. Audiences were like that too. CROUCHING TIGER was such a success. SPIDER-MAN came out and suddenly HULK was released in the wake of that blockbuster. I thought I had a good chance at taking something pulpy and making it serious and thoughtful, that I could give it psychology.

“I especially thought I could do that here, in the [United] States,” continued Lee. “In [this country] it is only through pretending that we can touch the truth. I thought this comic book would be a good way to do it. The problem with this film is that it spells out its psychology.”

Outside of the movie’s plotting issues, Lee said the psychology of American audiences at the time of the film’s release might have also played a role in HULK’s dismal box office. “Released during a war – with Middle Eastern music over desert scenes, its look at repressive memory and personal failure – American audiences may have purposefully chosen to ignore all of these factors,” Lee said. “They wanted to keep their [post-9/11 feelings] repressed.”

Lee recounted the film’s marketing campaign, which included former Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld’s yearning to show the film to American soldiers in Iraq. (The U.S. military played a key role in the battle footage of HULK.) Lee decided it wouldn’t be prudent. “I said [at the time that] it probably wouldn’t build morale,” he reasoned, with a laugh.

~~~~~

LEE STUDIED DRAMA at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign after flunking a college entrance exam in Taiwan. He decided to study something artistic in the United States. Until the making of HULK, Lee’s own father was discouraging.

“It took me eight films to get my father out of my system,” Lee said, jokingly.

Lee was “interested in both movie-making and stage work,” he explained, “and I actually wanted to become an actor. When my father suggested I come to America, it was because he thought at least with a degree [from] here, I would be able to fall back on teaching something.”

Lee said he “devoured movies in the United States. I saw so many of them. I don’t know how I ever found time to do my homework.”

Acting never panned out. Neither did stage directing. “Film became my medium,” Lee concluded.

Contemplating his expansive and eclectic filmography, Lee said he chooses to direct a variety of films across genres because he “makes a concerted effort to be true to what my heart tells me to make.” Shifts between genres – or, in the case of HULK, attempting to bend and bind genres – make his career “like one long film school.

“[Producers] are really paying me to learn,” Lee continued. “To make a new film is to learn a new genre and explore another part of yourself. To touch each and every genre is to actually learn a little more about that genre’s intended audience, their art, their lives.”

Lee said his favorite director is the late Ingmar Bergman. “When I saw his film, THE VIRGIN SPRING, I was a teenager in Taiwan,” Lee explained. “It was like someone took my virginity.”

Lee got to meet Bergman. “His last favorite film, he said, was THE ICE STORM,” Lee revealed, “my ‘fuck you’ movie.”

Lee concluded that time may make future generations perceive HULK differently. Lee also said the movie’s limitation to DVD and television broadcasts restrains HULK’s scale and scope. A revival at the Virginia Theatre, however, is “certainly a good start.”

“Television is Bruce Banner,” Lee said. “The screen here is the Hulk.”

~~~~~

Continue to “The Big Ten” pt.6

HULK is a production of Valhalla Motion Pictures/Good Machine in association with Marvel Enterprises distributed theatrically by Universal Studios and on DVD by Universal Studios Home Entertainment. It was directed by Ang Lee, produced by Gale Anne Hurd, Avi Arad, James Schamus, and Larry Franco, and written by Schamus, and stars Eric Bana, Jennifer Connelly, Sam Elliot, Josh Lucas, and Nick Nolte. 2003, 35mm, Color, 138 minutes.

~~~~~

“The Big Ten” pt. 5 © 2009 Anthony Zoubek. Used with permission.

CUBlog edit © 2009 Jason Pankoke

All graphics © 2003 Universal Studios,

courtesy of Roger Ebert’s Film Festival