Article du C-U: Ebertfest X, pt.4

“The Big Ten”

Roger Ebert’s Film Festival reaches the end of a decade – but without its founder and host

by Anthony Zoubek

~~~~~

Dateline – Champaign, Illinois

Friday, April 25, 2008

THE BEST FILMS AT the 10th annual Roger Ebert’s Film Festival were enigmatic and prophetic, capitalizing on the ambitions of filmmakers remaining true to the vision of their work – even in the face of the financing issues, distribution mishaps, and audience misconceptions plaguing their films upon initial theatrical release.

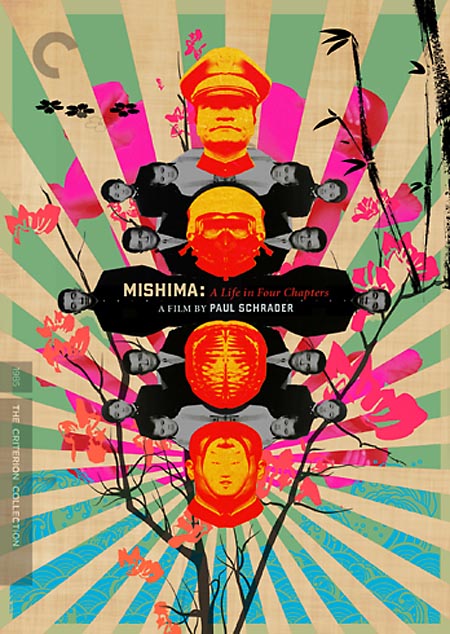

Paul Schrader’s MISHIMA: A LIFE IN FOUR CHAPTERS (1985) closed out a long Friday evening of filmic festivities. Chaz Ebert, taking the stage on her absent husband’s behalf, noted the 10 p.m. start time and the remaining, near-sellout Virginia Theatre crowd there to watch Schrader’s little-known masterpiece, the very best movie screened this year.

“This is the hardcore audience,” Chaz said. “Whether the films are funny, challenging, dramatic, you stay.”

Among the night’s special guests was Schrader himself, bringing a private print of the film, which – long out of print – earned a deluxe DVD release during the summer thanks to The Criterion Collection, “the guardians of cinema,” per the director. Also in attendance was, to use Chaz’s vernacular, “the elegantly multidisciplinary” designer Eiko Ishioka, internationally acclaimed for her stage, film, advertising, and graphic designs. Ishioka provided the intensely moving visual ambiance that gives MISHIMA its organic pulse. Notably, Ishioka won an Academy Award for costume design on Francis Ford Coppola’s BRAM STOKER’S DRACULA (1992) and has also worked closely with filmmaker Tarsem Singh, whose image-orgasmic THE CELL would play “Ebertfest” on Saturday evening.

As was the case prior to the festival-opening screening of HAMLET, film scholar David Bordwell discussed the intellectual command the movie takes over its audience. “In film circles, the 1970s are always talked about as film’s last Golden Age,” Bordwell said, “but I also like to look at the 1980s. In some ways, these films are bolder than the 1970s trailblazers.

“The 1980s were not just about the blockbusters,” Bordwell continued. In some ways, the stigma of “Eighties films” makes “determined movies like MISHIMA that much more underappreciated.”

Bordwell explained Schrader’s importance to cinema “as a writer and a film critic” as much as the screenwriter of TAXI DRIVER (1976), RAGING BULL (1980), and THE LAST TEMPATION OF CHRIST (1988). Specifically, Schrader’s “critical writing is a major contribution to our understanding of cinema,” Bordwell said, citing Schrader’s article on film noir as “the best ever written on the subject.”

Schrader’s body of work, with MISHIMA providing the best example, makes a case for films giving us “glimpses of a world that is tangible,” Schrader said. “That is, a world that harbors a seemingly untouchable or indefinable Zen, but remains tangible,” giving “physicality to the spiritual” and duality to the “harmony of pen and sword.”

~~~~~

AGAIN, THE OPPORTUNITY FOR the audience to screen the filmmaker’s personal print – a true director’s cut – lent itself to the event-status brought to most of the movies shown at Ebertfest. The crispness and clarity of the moving image made clear how little the film has been seen since 1985, and the loving care with which Schrader put together and continues to take care of his creation. The movie lived up to any expectations of being, as Bordwell previewed, “one of the most unusual and penetrating experiences any of us are likely to have at the movie.”

MISHIMA is the unconventional biopic of Yukio Mishima, Japan’s most celebrated author and playwright, whose novels made him the Ernest Hemingway of the East. But Yukio’s works, including Temple of the Golden Pavilion, Kyoko’s House, and Runaway Horses, were relatively unheard of in the West. His central themes, relative to the dichotomy of traditional Japanese values and spiritually-barren contemporary life, were also relative to Yukio’s own inability to find spiritual well-being, unable to align himself with traditional values in the face of his own bisexuality and masochism.

A writer during the same era as literary provocateurs Gore Vidal and William Faulkner, Yukio yearned for the same self-promotional “pop idol” status afforded them as well as struggled with his lack of celebrity status in a country vastly changing due to the impact of Western culture – visualized through the blossoming technology of television. For example, Vidal is a recognizable, reputable figure among audiences who never read any of his works thanks to the small screen. (At one point in MISHIMA, a reporter asks Yukio, played by the late Ken Ogata, who he “would like to be.” His response, indicative of television and American culture, is “Elvis Presley.”)

Yukio conceives his life and work as two defining but diametrically opposing forces that must somehow reflect each other. He ultimately forms his own “private army,” the Tatenokai, a political militia budding with young men meant to appease more than just the author’s buried sexuality. On the last day of his life – on which he intends to finally link his powerful literary work with what he perceives to be a celebrity-making message – Yukio and four members of the Tatenokai visit the headquarters of the Eastern Command of Japan’s Self-Defense Force. With an Eastern Command leader tied up to a chair, Yukio commits seppuku, a meticulously rehearsed suicide by self-disembowelment, immediately followed with his decapitation by a Tatenokai member.

“All my life, I have been acutely aware of a contradiction in the very nature of my existence,” Yukio explains. “For 45 years, I struggled to resolve this dilemma by writing plays and novels. The more I wrote, the more I realized mere words were not enough. So, I found another form of expression…”

~~~~~

MASS MEDIA ALLOWS AUTHORS to become media stars. A writer’s work is no longer confined to the printed word. Yukio was one of the first writers to seize the notion that media makes life an artistic product, and his biography – at its beginning and its end – was metaphysically entwined with the themes of his literature. His inability to entwine the public’s perception of his art with the artist is envisaged by Schrader and Ishioka’s vibrant use of three distinctive layers: Yukio’s life, his art, and his self-aggrandizing finale.

Flashbacks to Yukio’s coming-of-age are shot in strikingly rich, high-contrast black-and-white. In stark disparity, we see Yukio’s last day on earth, as he mounts his political statements and prepares for the death he hopes will bring him infamy, in realistic cinema vérité and color. Highly-stylized adaptations of scenes from Yukio’s narratives – shot on a soundstage with minimal, richly textured props, exaggerated to highlight the theatre of the writer’s creative non-fiction – are inserted at key moments to draw thematic links between the writer’s dramatic inventions and how the multi-interpretable truths embedded in those inventions lent themselves to his misguided reality.

Yukio’s biography remains in balance with Schrader and Ishioka’s brilliantly overt and artful interpretation of an author who writes with purpose, even though his life struggles leave him without a sense of purpose.

During a post-screening question-and-answer session, Schrader said he made the film after becoming “enamored by the idea of suicidal glory – of suicidal sacrifice.” He also said he reflected on his experiences writing TAXI DRIVER, the Martin Scorsese classic about a desolated, lonely, uneducated American male looking for blood-bathed celebrity, and was intrigued by the fact that, as a protagonist, Yukio “is the same exact guy. To make a movie about the West and then go to the East and talk about a writer – an intellectually accomplished man, supposedly the antithesis of Travis Bickle – we find that we still get a person interested in suicidal glory.”

In telling the story of a writer, “I had to tell the stories of their fantasies,” Schrader explained, citing the visual compartmentalization of the three biographical attributes of the movie. The film had to have several distinct, dissimilar, juxtaposed tones because “Mishima, as a man, was compartmentalized. He went from one part of his day to another – from the structured crosshatching of themes across three novels – that come out of a compartmentalized life.”

Much of the movie’s style, Schrader admitted, was born not just out of thematic visualization but also out of problem-solving – aspects of the story were stylized to make them cinematically palatable. “Inspiration is just another world from problem-solving,” he said. “The graphic design of the film was actually born of problem-solving.”

Ishioka said that Ebertfest marked “the first time I’ve seen the film on a big screen since 1985.” At the time of its making, she was not a professional film designer and had only directed a few television commercials and designed some live theater. MISHIMA was “a very serious, very intellectual film,” she continued. “My feeling, that I created this film, was like being a blind horse running under Paul’s direction.

“He demanded I design for the parts of the film that take place in 1950s Japan,” Ishioka continued, “a time when Japanese culture was being influenced by America’s ‘bad taste’ culture [as portrayed] on television.” In line with the film’s allusions to Yukio’s culture shock, she had to be in the mind set of “imitating Japanese bad taste culture imitating American bad taste culture imitating real American culture.”

This, concluded Bordwell as moderator, “almost exclusively visually tells the story of the history of Japanese popular culture and politics.”

Agreeing, Schrader said Yukio was “defined by a need to be loved by the West,” noting that the perception of the West is itself defined by “the great lie that is the movies.

“Film manufactures reality,” Schrader continued. “We get two hours of manufactured reality. In life, what we really have are conundrums without resolutions. [In MISHIMA] what we get is a two-hour exploration of conundrums – without resolutions – that at least helps us understand the conundrums better.”

~~~~~

MISHIMA WAS NEVER released in Japan.

“There, it’s a consensus culture,” the director said. “In Japan, there is little agreement on Mishima because no one can agree on Mishima. The artistic community of Japan has seen the movie, or is at least aware of it. The general public has not.

“When the film was effectively banned, people did not seem to mind it because it meant they wouldn’t have to see it [nor] formulate any opinion,” Schrader explained. “I remember when there was a possibility of releasing the film in Japan, we had a promotional dinner; purposely, no one talked about Mishima.”

Schrader said that, of all the films he’s made, MISHIMA is his favorite “because it’s so damn peculiar.”

The movie was “made by fools,” he opined. By 1980s blockbuster standards, MISHIMA was financed on a shoestring budget that few, except producers Francis Ford Coppola and George Lucas, were willing to admit they helped compile.

“Essentially,” Schrader quipped, “the movie was made by no one.”

~~~~~

Continue to “The Big Ten” pt.5

MISHIMA: A LIFE IN FOUR CHAPTERS is a co-production of Zoetrope Studios/Filmlink International/Lucasfilm Ltd. distributed theatrically by Warner Bros. and on DVD by Warner Home Video (2001) and the Criterion Collection (2008). It was directed by Paul Schrader, produced by Mataichiro Yamamoto and Tom Luddy, and written by Paul Schrader, Leonard Schrader, and Chieko Schrader, and stars Ken Ogata, Masayuki Shionoya, Hiroshi Mikami, Junya Fukuda, Shigeto Tachihara, and Junkichi Orimoto. 1985, 35mm, Color/B&W, 121 minutes.

~~~~~

“The Big Ten” pt. 4 © 2009 Anthony Zoubek. Used with permission.

CUBlog edit © 2009 Jason Pankoke

All photography courtesy of Schrader Productions,

artwork courtesy The Criterion Collection