Article du C-U: Ebertfest X, pt.3

“The Big Ten”

Roger Ebert’s Film Festival reaches the end of a decade – but without its founder and host

by Anthony Zoubek

~~~~~

“I AM AN EBERT, BUT I’M no Roger Ebert,” Chaz Ebert told the Virginia Theatre audience prior to the screening of HAMLET.

Chaz explained that, during the recent trip to Florida – a venture on which Roger began strengthening and conditioning himself to be in fit enough condition to attend the festival – her husband’s hip “went one way while the rest of him went the other.” To not have him at Ebertfest surely leaves all of us “to borrow his words, a bit melancholy,” she said.

“But this festival is five days long,” Chaz continued, “and hope springs eternal. Right now, he’s in the right place at the wrong time. I’m sure he hopes you enjoy the festival as much as he enjoyed putting it together.

“Let’s beam all of that positive energy,” she added, citing her “new age” perspective. “Let’s see if we can get him here soon.”

Chaz led the audience in a “Get well, Roger!” chant, repeated by David Bordwell – much louder – later in his pre-screening remarks.

“I think he heard us,” Bordwell said with a smile.

~~~~~

EBERTFEST IS a product of the College of Media (formerly the College of Communications) at the University of Illinois, and its presentation of HAMLET was sponsored in part by the Tawani Foundation and the Pritzker Military Library. Their contributions – in conjunction with the monetary donations of a variety of other sponsors – help keep the cost of Ebertfest passes at an affordable price for the general public that make Ebert “the people’s film critic.”

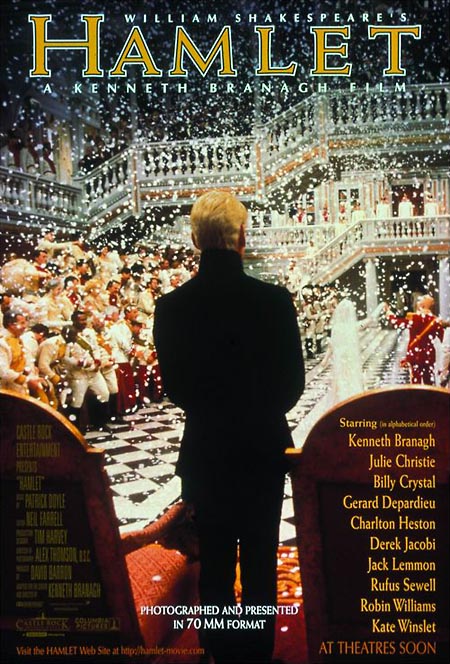

With this production of HAMLET – the most complete film adaptation of William Shakespeare’s work, it clocks in at 242 minutes and is one minute short of being the longest movie in history – Kenneth Branagh “inherits the mantle of [Lawrence] Olivier and [Orson] Welles,” Bordwell explained.

“Branagh provides an interesting flavor of contemporizing Shakespeare,” he continued, “not just by mixing well-known British actors and American stars,” but also by exhibiting “a modernizing visual impulse,” referring to the film’s use of highly stylized zooms and pans amidst material written to be staged live for audiences.

The film is also unique, said Bordwell, because of the accessibility Branagh gives to the delivery of dialogue, spending much of his time directing his performers to use “exact diction,” because “Shakespeare actually becomes intelligible – not dense – if you say his words precisely.”

That the film was shot and exhibited in 70mm manages to accentuate both its strengths and weaknesses in visual showmanship. The movie’s interiors – filmed at the Blenheim Palace in the United Kingdom – take on a look so bold and textured that the aesthetics become as much of a bombastic character as Branagh’s Hamlet can be. The 70mm photography of Branagh in his most eloquent and quieter moments bring a lively visual complexity to what is already one of the world of literature’s most influential “collegial coming-of-age” stories of all time.

However, when exhibiting Branagh’s loudest and most overactive moments, 70mm heightens the extremes to which Branagh’s interpretation of the character tends to go over the top. This is often because, though not entirely excused by, the Hamlet character’s desire to make others think that he has gone mad. Luckily, the profundity other actors take in churning out every ounce of depth in even the most minute of roles – the best being Billy Crystal as a gravedigger – make Branagh’s occasional inconsistencies ignorable.

Interestingly, it is the film format alone, consistently capturing the three-dimensional quality of the movie’s mise-en-scene, which calls attention to Branagh’s strengths as a director and actor. Such potencies help Branagh overcome the flaws of his own film which, ironically, the photography helps call attention to in the first place. Bordwell’s line of praise of Branagh’s 70mm approach – that “the use of widescreen allows us to literally encompass the extensions of Branagh’s production” – is also an applicable criticism of the film.

Flaws aside, the raw power of Shakespeare’s challenging tragedy brought most festival attendees to their feet for a rousing round of applause upon the movie’s conclusion. I agree with Ebert’s own assessment in his original review of the film; as Hamlet takes his place in the larger context of royal politics, the greatest benefit of a full-length version is that other characters (even those who, in previous adaptations, served only as background) are given rich opportunities to be fleshed out and understandable.

Following the film, actor Timothy Spall, who played Rosencrantz, and Rufus Sewell, who played Fortinbras, talked specifically about the potency of this particular aspect of Branagh’s interpretation. The film illuminates “even its bit characters,” Spall explained. “Every actor thinks that the film’s all about them anyway, even if they only have one line. Branagh [capitalized] on that.”

Sewell surmised that his seemingly time-consuming role in the film actually took a day to film. He came to the set and filmed his part even before principal photography on the movie began. “Branagh had me come in before the start of [the shoot],” Sewell recalled. “He’d say, ‘Now, look over there … now, look over there … look angry, everyone’s dead.’ Then he cut that footage into and throughout the whole movie. It was an afternoon’s work.”

Chaz Ebert upheld another Ebertfest tradition by giving Sewell and Spall each a Golden Thumb Award – gold casts of her husband’s hand with the thumb raised high.

~~~~~

Continue to “The Big Ten” pt.4

HAMLET is a production of Castle Rock Entertainment distributed theatrically (U.S.) by Columbia Pictures and on DVD (U.S./U.K.) by Warner Home Video. It was adapted for the screen and directed by Kenneth Branagh and produced by David Barron, and stars Branagh, Derek Jacobi, Julie Christie, Kate Winslet, Richard Briers, Charlton Heston, and Timothy Spall. 1996, 70mm, Color, 242 minutes

~~~~~

“The Big Ten” pt. 3 © 2009 Anthony Zoubek. Used with permission.

CUBlog edit © 2009 Jason Pankoke

All photography © 2007 Warner Home Video,

artwork © 1996 Castle Rock Entertainment/Columbia Pictures