Q&A du C-U: Bender & Bakkila

“The Witch School Film Project”

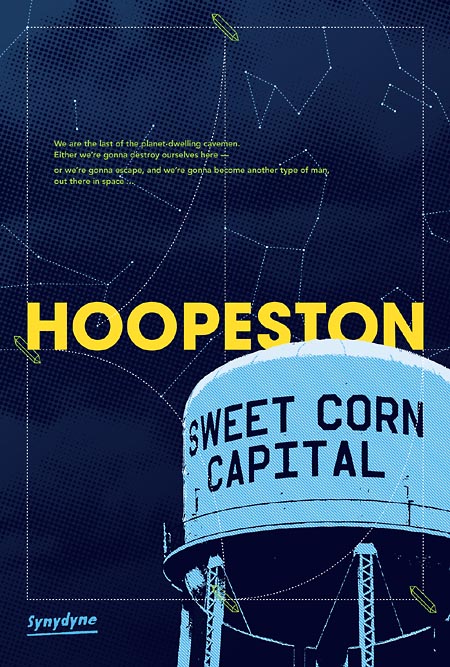

An interview with Thomas Bender and Jacob Bakkila of HOOPESTON

by Jason Pankoke

As an undergraduate at Illinois Wesleyan University in Bloomington, I would often hear my peers refer to our school as “the bubble.” This convenient metaphor, implicit throughout our small campus by the iconic arched window that serves as an IWU indicia, had been used time and again to call out the student body (in effect, ourselves) for living an insular academic life while the larger issues of our world resided elsewhere. Sadly, I’ve noted variations on that once-shallow idiom ever since. Even when one is busy taking care of life’s needs and striving to contribute to one’s communities, one is often oblivious to dynamics operating across the county line, barely a mile down the road, or aggravatingly just out of reach.

In my 15 years as a Champaign resident, I’ve given little thought to Hoopeston, Illinois, barely an hour drive from here but seemingly worlds away. Called the “Sweet Corn Capital of the World” in its 20th century prime, this depressed farm-and-factory town may have been indistinguishable in the eyes of New York filmmakers Thomas Bender and Jacob Bakkila if not for the introduction of an eccentric element foreign to Hoopeston’s old-fashioned aura. The resulting documentary, HOOPESTON, is less about its namesake and more the tenacity of its folk while a storyline that seems primed to detail a literal, modern-day witch hunt instead lopes off the expected path to provide a gently haunting exposé on current prairie Americana.

Once again, it takes the keen perception of someone green to Champaign, Urbana, and the cities beyond to provide us with a colorful look back at ourselves.

Read on, Sweet MacDuff…

Jason Pankoke: Jake and Tom, we thank you for working us into your schedules for this third-ever “EXTRA!” interview for C-U Blogfidential. I’d first like to know about your personal backgrounds…

Jacob Bakkila: I went to college at the University of Southern California (USC) for print journalism and worked as a fact-checker at the Los Angeles Times for the better part of a year. I’ve since moved away from journalism and into creative Web content. I live in Brooklyn.

Thomas Bender: I studied physics at Princeton and then tutored in New York until I could afford to shoot HOOPESTON. After that, I started working as a video editor and spent about a year piecing together the movie at night.

JP: Then, what inspired you to start making your own movies in the first place?

TB: I watched VERNON, FLORIDA, one of Errol Morris’ early films. It’s impossible to watch that movie and not want to go make a documentary.

JP: Is there a relationship between Morris’ accomplishment with that film and what you initially hoped to capture for the camera in Hoopeston, Illinois?

TB: Yes. That one and GATES OF HEAVEN, his first film, are my favorite movies. Both have incredible stylistic confidence, especially in the way the interviews are shot.

JP: Which earlier projects in your careers would you consider the most significant leading up to the production of HOOPESTON?

TB: Before HOOPESTON, I had done two experimental documentary shorts. I didn’t know very much when I made HOOPESTON. It was a learning experience.

JB: As I did the interviews for HOOPESTON at [age] 22, I don’t have too many earlier works to cite.

What most influenced my style of interviewing was my undergraduate experience at USC. In particular, I was fortunate enough to have two classes with Ted Rohrlich, a superlative investigative journalist who I believe recently left the Times. Among the volumes he taught me was the simple truth that, as a journalist, it is your responsibility to act as a witness. It was an uncomplicated lesson dropped among many long nights of city council reporting, but it was the most important thing I learned in college.

With this in mind, I was always careful in each interview for HOOPESTON not to allow myself to dictate what the story was about, but rather to do my best to bear witness to each subject’s personal experience as it related to the objective timeline of events that made up Hoopeston’s history.

JP: What were your first impressions as New York residents stepping into this small-town Midwest community? How much did you know about Hoopeston going in?

TB: Going in, I knew only what I had read about Hoopeston’s cheap real estate and the Witch School. My first impression was that it was its own small world. Everyone seemed to know everyone.

JB: We knew practically nothing about the town, mostly because it wasn’t very easy to dig up information outside of the community. But, we took learning about it very seriously when we arrived.

JP: Despite the primary attraction to your project being the Witch School controversy, there are deeper undercurrents and issues plaguing the Hoopeston of today – so much so, that the documentary is compelling from the start even though Wicca or the school aren’t brought up until (curiously) the 13th minute.

TB: I initially expected the story to be about the Christian/Wicca controversy, but that ended up only being one part of it. It wouldn’t have been right to open the movie with that; I thought it was more important to give a sense of the town in the beginning. Also, I like the slow, understated reveal of the witch [material] as part of the “Real Estate” section, but I don’t know whether it works or not. People might find that exposition boring. [HOOPESTON is “a video documentary in four parts,” which includes “Decline,” “Real Estate,” “Religion,” and “The Crystal Web.” – ed.]

JP: I believe the gradual build-up to the Big Questions works well. Once Ed Hubbard and Don Lewis of the Witch School are introduced, you have a segment lasting several minutes that contextually sets up a lot of what is covered throughout the running time, coming from the mouths of key interviewees. Some quotes that I thought were rather pointed include the following:

“If you ever sit out and watch this little liquor store that has a drive-through window, the line never stops there. People cash their checks there and buy their Lotto tickets and get their Jack [Daniels whiskey] and Coke. That’s their mentality.” – Jason Matthews, Downtown Hotel, Hoopeston

TB: Jason paints a fairly grim picture of Hoopeston life with that quote. It’s not like everyone was a depressed alcoholic, but circumstances are definitely tough. There aren’t a lot of jobs. Jason told us that a lot of people go into the military, then come back and take up drinking.

JP: “There are a lot of people in this town who don’t want it to change. They want it to be what it was. They want to see the factories come back, they want the world that was 20 years ago.” – Most Reverend Donald Lewis-Highcorrell, the Witch School

JB: Sage insight from Don. You could trace this to a lot of the film, but to me it’s best illustrated by the entire Wildon Building [in downtown Hoopeston], which we show in a montage. Loni Gress let us in there to poke around and film, and we were amazed. As the town’s economy turned for the worse, businesses moved out from what seemed to be the top downward, so each floor acts as a time capsule of sorts.

If I remember correctly, the second floor has burgundy carpeting and wood paneling, while the top floor has rooms that belong in an old detective pulp from the 1950s, down to the decades-out-of-date Sweet Corn Festival sticker that we found. [It’s] a very beautiful building and a simple, effective representation of the town’s decline.

JP: “When you go to start something here, everybody’s against you, the whole tide is against you. Because, the first thing they want to know is, where you from, where you at, what you’re offering, and what’s your religion. If you’re not Christian, and if you’re in Hoopeston – you can ask the pagans – they will try and run you out.” – Jason Matthews

TB: Everyone in the town wasn’t trying to run out “the pagans.” When we were there, the Witch School folks weren’t experiencing any serious opposition; most of that happened during their initial move-in. A lot of people talked about a resistance to change in Hoopeston, but most people we talked to didn’t care about the witches. Everyone was worried about the economy.

JP: What types of things did the townsfolk touch upon, then? Did they offer up specific thoughts on how this situation could be reversed or improved upon other than wishing for “the way it was”? I could see where interviewees might have held back so as not to amplify the dire straits for the camera.

TB: They all said the town needed jobs. People had different ideas about how to bring them in, like starting a business incubator or expanding the Sweet Corn Festival. I don’t think anyone held back. Everyone agreed that things were pretty bad.

JB: There were a lot of ideas mentioned from a variety of subjects about different business possibilities. For example, a museum in the Wildon Building, if I remember correctly, and Ed Hubbard was planning on starting a high-speed wireless Internet company. While there certainly was a wistful attitude toward Hoopeston’s past, many people were trying to make things better. But, in that type of town, wide change is difficult and takes time.

JP: The Sweet Corn Festival does seem to be the one bright spot as depicted in HOOPESTON, an elaborate celebration that harkens back to mid-century Americana with the pageantry, carnivals, and everything else.

TB: Everyone we talked to brought up the Sweet Corn Festival. It’s the pride of Hoopeston, and it was moving to experience it. I don’t want to analyze it too much. You should go. It happens at the end of August.

JP: While it could be claimed that Hoopeston’s citizens reflect early and often on this long-standing tradition to deflect attention from their plight, both Donald and Ed act relatively forthcoming about discussing their faith and backgrounds in the film. Did any moments from their interviews enlighten you or catch you off guard in regards to modern paganism or the specific “tradition” they’ve fashioned to fit their needs?

JB: It took me a lot of interviewing to get Ed and Don to open up as much as they did. Each of their interviews lasted at least three hours with no break. I leave analysis of what each of them said up to the viewer, but I will say that the way they participated in the interviews was enlightening on its own – Don’s seamless transition from formal to informal, placid to frustrated; Ed’s start-and-stop stream-of-consciousness storytelling. How each of them communicates, I think, gives reasonable insight into their specific personal values, as well as how each views his role in their dyad.

JP: I was actually surprised to see so much of their “home movie” footage incorporated into HOOPESTON. At what point did you first get to see this material, and how did you decide which segments made it into the final cut?

JB: We got the material a few months after we were done shooting. Since Tom was busy actually editing the film, I took care of trying to make sure we had enough supplementary footage, like the news video, and anything Witch School could offer us. I made it clear to Ed that we’d love to see whatever they had to send us, but we were especially interested in shots of ceremonies as well as footage of everyday life.

When Tom got the footage in the mail, he told me to come down to the city to watch some of it, so I did. (I lived in Ithaca at the time.) Simply put, I was extremely surprised both to see how much they gave us and how candid they were in their selections. Additionally, so much of that “found footage” from Ed acts as the perfect supplement, both visually to Tom’s directing and shooting style and materially to the information gathered in interviews.

TB: Ed and Don were very generous with what they sent us which was lucky because, frankly, I didn’t shoot nearly enough material in Hoopeston. It was easy to choose which segments made it into the cut. I just picked the interesting parts.

JP: At the same time, all the faces of the initial opposition to Witch School establishing itself in Hoopeston, the local pastors and church members from other denominations, are scarcely present in the film aside from a bit of B-roll. Was there still so much reluctance to discuss the issue after the brouhaha, even on camera?

TB: That’s true. All the Witch School opponents we reached out to refused to go on camera. We called every pastor of every church in town. That said, most people seemed ambivalent when we were there [to shoot]. The controversy ended up being a minor part of the story.

JB: Plus, it’s a small town, word travels quickly, and since there’s only one hotel we weren’t too hard to find. If anyone wanted to talk to us about the Witch School, they certainly had a reasonable chance. We weren’t going to try to “ambush interview” anyone; silence is just as valid a response as talking.

JP: I like how the documentary gives time to Doug Hickman of Universal Ministries, who comes from an old tradition of starting from the ground up a congregation in rural America – in his case, Hoopeston neighbor Milford – with gusto and charisma, not to mention a little contemporary savvy given the interesting cyber-spin to his church’s growth. His presence brings a de facto third side to the story when it comes to the film discussing beliefs and religion.

TB: Doug Hickman is amazing. I wish we could have given him more time. It was lucky to find the parallel story of a second new religion that exists primarily on the Internet. He and Don even used the same expression, the “spiritual two-by-four.”

JB: Doug was a fantastic interview. We could not have been more fortunate that our “third side of the story” for Hoopeston happened to be a charismatic, gracious, and sincere heartland cyber-minister.

JP: Did you find in your interviews, both on- and off-camera, that Hoopeston citizens felt their religions held the answers for solving the town’s ailments, or did they exhibit a defeatist nature about the circumstances?

TB: Neither. People were reasonable.

JP: To that end, Don and Ed never address the ills in terms of how they may or may not affect Witch School, or how their efforts might actually help Hoopeston itself apart from providing jobs to a few individuals. Despite Don’s prescient observations such as the earlier quote, did you ever notice disconnect in this regard?

TB: Ed and Don weren’t dependent on the local economy; Witch School does its business on-line.

I think Ed felt the town could recover if it embraced the Internet and he saw Witch School as the first step in that direction.

JP: With all that is said and pondered during HOOPESTON, you were able to evoke a rustic timelessness that is simple and evocative. I really enjoyed the camerawork because it lends the project an honest cinematic quality that you rarely see in a documentary regardless of budget. The place certainly looks livable if suburbia is not one’s style, despite the economic woes.

TB: Thanks. I think I prefer wide, static shots because I’m so bad at hand-held shooting. Aside from the found footage, the camera almost never moves in HOOPESTON. The couple of vérité segments I did try to shoot didn’t work very well.

JP: On top of those visual qualities lies M. Todd Mazierski’s music score, equally spare but invoking a vaguely familiar mid-century flair that inspires no less than a few goosebumps upon first listen. It seems to yearn for another time, just like many of Hoopeston’s survivors.

TB: Todd did an incredible job. His score is the best part of the film. Some of his pieces, like the Wildon Building track and the Sweet Corn Festival track at the end, directly influenced the cutting.

JP: HOOPESTON has had staggeringly little play in the United States, most of it relegated to big-city film festivals no doubt attracted to the Witch School angle. It played the Windy City in 2008 at the Chicago Underground Film Festival, but has it shown elsewhere in the Midwest including Hoopeston itself? How have audiences reacted?

TB: I never really expected it to show anywhere, so I was delighted when a few festivals showed interest. Audiences seem to enjoy it, but they’re probably self-selective. If you buy a ticket to a lo-fi documentary at an underground film festival, you know what you’re getting into.

It hasn’t shown anywhere in the Midwest outside of Chicago, but we just put the whole thing on-line so anyone can watch it. It won’t have a DVD release.

JP: Since you finished filming, the Witch School has moved once again, this time to Rossville, IL, near Danville. Did you ever consider adding a coda to the documentary about this development?

TB: No. The end is my favorite part. I wouldn’t want to mess it up.

JP: That’s true. Dusk does seem to fall at the appropriate time in HOOPESTON, so I have to agree with you.

[Just this past December, the Witch School picked up once again and moved a much longer distance to Salem, MA. – ed.]

You’ve since returned to take a look at a more urban Midwest with THIS IS MY MILWAUKEE, which I understand is a work-for-hire and not a fictionalization of Brew City a la Guy Maddin’s MY WINNIPEG. It is attention-grabbing in its sheer strangeness and I enjoyed it greatly, but is it really promoting tourism in Milwaukee, WI, or is it a parody of duller-than-dirt promotional videos?

TB: It’s actually promoting Milwaukee tourism. At the moment, we’re working exclusively with the Milwaukee Tourism Commission.

JP: Finally, the penultimate Hoopeston question I’d like to ask is, did you take in a movie at the Lorraine Theatre while you were there?

TB: No, we were working constantly and there wasn’t time. I don’t even remember eating.

Interview conducted December 2008-April 2009 via e-mail.

All photos courtesy of Thomas Bender/Synydyne.

HOOPESTON is a production of Synydyne. It was directed by Thomas Bender and produced by Jacob Bakkila and Thomas Bender, and features Ed Hubbard, Jason Matthews, Domingo Arredondo III, Mark Drollinger, Loni Gress, Doug Hickman, Bill Dewitt, Catherine Novak, and the Most Honorable Reverend Donald Lewis-Highcorrell. Running time is 78 minutes.

CUBlog EXTRA! Interview No.3 © 2010 Jason Pankoke